Third, you need to ‘own the code’ even if the AI produced it. Don’t think that because AI produced the code it’s not yours. The AI tool doesn’t care (or know) about the intention of the code it is producing on your behalf. Even though you didn’t write it, the code is yours in the sense that it is doing (or is trying to do) what you want it to do. As a human it seems intuitive that the AI should understand the code given that it produced it, but it really doesn’t. I found that only by accepting that the code was mine, including any errors in it, could I properly interrogate it to check for errors. But also, if I’m going to use the code for any practical purpose, then it’s my name against the outcomes, so the sooner I take ownership the better.

Code Development Wasn’t Always This Interactive

I’m so old that I learned to code from a book. Like this one:

Not very interactive. Back then, if you were feeling brave, for a bit more interactive help you could post on something like the R-help forum.

Now we’re in the era of generative AI and tools like GitHub Copilot and Amazon Q offer seemingly magical abilities (to a duffer like me) to interactively develop code. I’ve put off getting stuck into understanding how to use these coding tools, but this summer it seemed like I couldn’t put if off any longer (not least because my students are getting ahead of the game with it).

A Cellular Automata Case Study

So, I set myself the task of reproducing a simulation model, and it’s results, from a peer-reviewed paper. The paper I chose was Evolution of human-driven fire regimes in Africa by Sally Archibald and colleagues. I decided to ask GitHub Copilot (hereafter ‘copilot’) to reproduce this model because:

- I would have a way to know when I had succeeded, by comparing my outputs to the results the original authors found, and;

- I’m interested in this subject area and maybe I could build on the original model to investigate new questions.

You can find the code along with revision history on GitHub here (v1.0 is the state of the repo at the point of the first working ‘vanilla’ version of the Archibald et al. (2012) model – i.e., without any additions). I started interacting with copilot via the GitHub webpage in a browser (see that interaction history here) but then moved into the VS Code IDE with copilot in the chat sidebar (I haven’t yet worked out how to share that session).

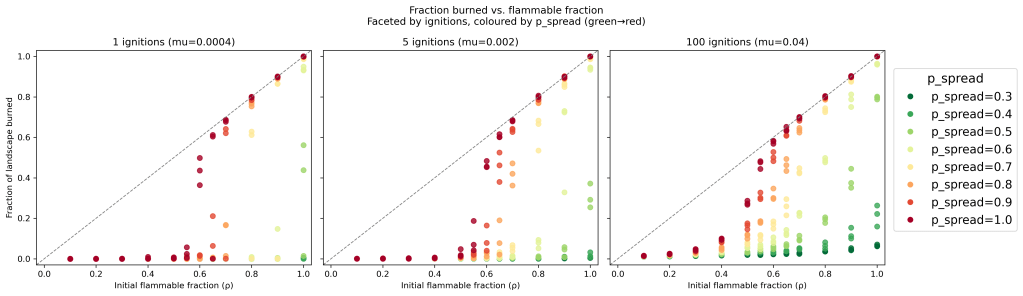

Over the course of about 1.5 days I was able to develop what I think is an accurate replica of the original model, complete with code to produce data visualisations. How do I know it’s a good replica? Well, visualisation of data outputs match very well with what was presented in the paper (compare this output with Fig. 2 of the original paper – as shown below) and as you can see from the description of my interaction with copilot below, I had to reason through how the code was working quite carefully to produce those outputs.

Rather than go through the details of the copilot code development process at this point, first here’s a summary of my thinking about generative AI for coding (at the current time, summer 2025) from the whole experience.

The Good and The Bad

What copilot was good at:

- quickly generating foundational structure of code for simulation

- suggesting ways to test code at a low-level (e.g. individual lines of code or small functions)

- producing appropriate code for data visualisation

What copilot was bad at:

- getting the details of algorithm function to correctly match intention

- knowing (or ‘admitting’) when the code is not working as the human user intended

- interpreting high-level code function for errors (e.g. large or recursive functions and/or interactions between functions)

In short: co-pilot speeds up code development, but with errors.

To guess, I reckon it would have taken me more than a week to get to state we were in after 1.5 days. So saving 3.5 days is pretty good. What the time saving for others would be probably depends on their coding level, because, as my summary of the interaction below shows, I spent a fair bit of time debugging the code copilot was producing. Of course, I would have spent time debugging my own code, but co-pilot was just much faster at producing the code in the first place.

Consequently, given that copilot really is a code co-production tool (it’s in the name!), production time will depend on how good your code development skills already area.

What You Need To Know

It seems to me that to use something like copilot effectively (in its current, summer 2025, state), you need to know:

- what outputs you want (so that you can tell the generative AI what it should do)

- the mechanisms to produce those outputs (if mechanisms are important to you, as they were in this modelling case)

- what the outputs should look like if the code is correctly implemented (or at least what it should NOT look like)

So, in some ways this follows similar steps to the core elements of Peng and Matsui’s ‘epicycle of data analysis’:

- set expectations

- collect information or data

- compare 2 to 1

If 2 and 1 match, great, move on to the next question! If not, revise expectations or collect new info/data

In our case, using generative AI we have:

- work out what outputs you want (this is your expectation)

- provide the AI with a prompt to produce that output

- CAREFULLY compare the output of 2 to 1, including code tests where appropriate

My Three Key Takeaways

Which leads me to three three key things you currently need to bear in mind when using generative AI for code development.

First, you need to be wary of the AI insisting it is correct (i.e., that the output of the prompt matches what you expected or wanted) when the evidence is to the contrary. Or you have no evidence (if that’s the case, then get some evidence).

Second, you need to think about what the evidence of being correct is, get that evidence and test the code against it. If you already have the output you want to reproduce, that evidence is straight-forward (as was the case for me here, comparing my data viz against Fig. 2 in the Archibald paper). If not, you need to think about how you can check the code is working – what roughly should a visualisation of the output look like and/or what should it not look like. And for more complex code, what tests can you run on components of the code to check they are working as intended?

Third, you need to ‘own the code’ even if the AI produced it. Don’t think that because AI produced the code it’s not yours. The AI tool doesn’t care (or know) about the intention of the code it is producing on your behalf. Even though you didn’t write it, the code is yours in the sense that it is doing (or is trying to do) what you want it to do. As a human it seems intuitive that the AI should understand the code given that it produced it, but it really doesn’t. I found that only by accepting that the code was mine, including any errors in it, could I properly interrogate it to check for errors. But also, if I’m going to use the code for any practical purpose, then it’s my name against the outcomes, so the sooner I take ownership the better.

To see how I arrived at the points you might find it useful to read or explore some of my interaction with co-pilot. A summary of the journey to replicating the Archibald model is below, and a notebook showing the stages of co-producing the code for data visualisation is here.

Copilot and James: A Code Co-Development Story

To get started, I prompted:

“I want to reproduce the cellular automata model described in the following page using python. The model I want to reproduce is the one presented in this paper: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1118648109 Can you provide a starter template please”

After clarifying that the paper I actually wanted to reproduce [copilot somehow decided I wanted to reproduce a model from a different paper], within a minute or so I had a couple of hundred lines of code that looked like they could run some kind of simulation with visualisation. Pretty impressive! It would have take me a day or more to do the same I reckon.

Copilot even told me how to run the model:

To run the provided Python code for the cellular automata fire model, follow these steps:

- Copy the Code into a File

Copy the Python code from the previous response into a file named, for example, fire_ca_model_archibald2012.py.

- Install Required Libraries

The code uses numpy and matplotlib. If you don’t already have them installed, open a terminal (or Anaconda Prompt) and run:

bashpip install numpy matplotlib

- Run the Code

In your terminal, navigate to the folder containing fire_ca_model_archibald2011.py and run:

bashpython fire_ca_model_archibald2012.py

- What Should Happen The script will simulate the fire spread for a number of time steps.

After each time step, a plot window will pop up showing the grid’s current state:

Unburnt, burning, and burnt cells (distinguished by color).

You can close the plot window to proceed to the next time step or let it run automatically if you modify the plotting section.- Tips If you want the plots to update automatically without blocking, you can replace plt.show() with plt.pause(0.1) and call plt.clf() to clear the figure between steps.

For a faster simulation, comment out or remove the plotting lines.Let me know if you’d like the code modified for automatic animation or output to files!

In my next prompt, I said I would like the code modified for automatic animation. Copilot automatically updated the code – pretty slick! So now I was able to run the model and visualise some output (the animation).

From the animation and closer inspection of the code, the code wasn’t really doing what the originally published model did. Also, all the code was in a single file and now didn’t allow running the model without the animation. So I prompted:

“Wouldn’t it be better to have the ignition and fire spread simulation code to be separate from the animation code? e.g. if I wanted to run the model without animation. How to do that?”

Copilot replied:

Absolutely! Separating the core simulation logic from visualization/animation is a best practice.

And provided re-factored code. Notice how despite this being a ‘best practice’, copilot hadn’t already followed that best practice. You really have to keep coaching it along (but hey, this was still much quicker than me writing the code myself!).

So, next I prompted: “And then building on this refactored structure, how to add functionality to run batches of simulations with alternative parameterisations”

Copilot said:

Great question! With the refactored structure, it’s easy to add batch simulation functionality. Here’s how you can do it:

- Batch Simulation Function

Create a function that takes a list of parameter sets and runs the simulation for each set, collecting outputs (e.g., final grid, statistics).

- Example Implementation

Below is an example file that demonstrates how to run a batch of simulations with different parameter combinations and record the results.

- Notes Custom statistics: You can adapt run_simulation to return whatever statistics you want (e.g., time steps to extinction, spatial patterns).

Output: Save results to CSV or JSON for further analysis if needed.

Parallelization: For large batches, consider using Python’s multiprocessing for speed.Let me know if you’d like a version that saves results to file, or that uses more advanced batch/parameter management!

I prompted: “ideally parameters would be read from a file and results written to csv file. how do add this functionality to the current structure?”

And copilot gave me the code. Now I felt in a position to start revising the model structure as I had some way of varying input to check the outputs. So I prompted:

“We need to update the model so that not all cells are flammable and so that the user can define the initial proportion of the landscape that is flammable (this is parameter rho in the Archibald et al. 2011 paper that this code is emulating). How to do that?”

Now copilot really got going and provided code with properly defined functions. So at this point I thought I’d check how well co-pilot could explain what it was doing:

“when defining __init__ why do we then list a bunch of self. variables? What’s the rationale for this?”

Copilot said:

Great question! In Python, when you define the

__init__method of a class, you often see lines like:

class FireModel:

def __init__(self, grid_size, p_spread):

self.grid_size = grid_size

self.p_spread = p_spread

Why use self. variables in

__init__?The

__init__method is the constructor for your class. When you create a new instance (e.g., model = FireModel(100, 0.2)), Python calls__init__to set up that object.

What does

self.do?

self.is a reference to the current object (instance) being created.When you assign variables using

self.grid_size = grid_size, you are:

- Creating an attribute (variable) that belongs to this particular object.

- Storing the value so it can be used later in other methods of the class.

Why not just use local variables?

- If you wrote

grid_size = grid_size(withoutself.), you’d just have a local variable that vanishes after__init__finishes.- Using self. means the variable “sticks around” as long as the object exists, and can be accessed anywhere in the class (e.g., in

step()orspread_fire()).

Analogy:

Think ofself.variables as the “memory” or “state” of your model object. Each object has its own separate set of these variables.If you didn’t use

self.value,print_valuewould not be able to access value.

In short:

Assigning withself.in__init__stores information in the object so it can be used anywhere in the class, for as long as the object exists.

That’s a pretty clear explanation of how object-orientation fundamentally works in python, as good as I would have got in my old textbook. But it’s even better than a textbook, because the explanation is tailored to my code example.

Then I thought I’d see how well co-pilot does on the model logic and the code it had provided for that. Now it wasn’t so clear:

I prompted: “the new ignite function does not seem different from the previous version – explain how this new version differs from the previous version”

Copilot said:

Great question! The difference between the new ignite function (as I wrote it above) and the original version is subtle but important, and it’s all about handling non-flammable cells.

Original ignite (before supporting non-flammable cells):

def ignite(self):

natural = np.random.rand(self.grid.shape) < self.p_natural_ignition human = np.random.rand(self.grid.shape) < self.p_human_ignition

ignition = (natural | human) & (self.grid == UNBURNT)

self.grid[ignition] = BURNING

This version tries to ignite any cell that is currently UNBURNT.

It assumes that every cell can potentially be ignited (i.e., all cells are flammable).

New ignite (after adding non-flammable cells):

def ignite(self):

# Only ignite flammable, unburnt cells

mask = self.grid == UNBURNT

natural = np.random.rand(self.grid.shape) < self.p_natural_ignition human = np.random.rand(self.grid.shape) < self.p_human_ignition

ignition = (natural | human) & mask

self.grid[ignition] = BURNING

Now, only flammable and unburnt cells (i.e., those with the state UNBURNT) are considered for ignition.

Non-flammable cells (which have a different value, e.g.NON_FLAMMABLE = -1) will never be ignited because they don’t satisfyself.grid == UNBURNT.

The logic for natural and human ignition is unchanged, but it is masked so that non-flammable cells are automatically excluded.

In summary:

The new function ensures that only flammable cells (those with the UNBURNT state, not NON_FLAMMABLE) can ignite, which is essential after introducing non-flammable cells for the rho parameter. The masking step (mask = self.grid == UNBURNT) is what enforces this.

I wasn’t convinced and prompted: “Can you check your code again. Where in the new version does code change that non-flammable cells will not be ignited? if it is self.grid == UNBURNT this was also in the initial version, just a different location”

Copilot said:

You are correct: the crucial aspect is that the logic for not igniting non-flammable cells is enforced wherever you use

self.grid == UNBURNT. In the original version, all cells were assumed “flammable,” so “UNBURNT” meant “flammable and not burnt.” After introducing non-flammable cells (e.g.,NON_FLAMMABLE = -1), only cells withself.grid == UNBURNTare considered ignitable.

So, if the only check is self.grid == UNBURNT, then:

In the original version, all cells could be UNBURNT, so all could be ignited.

In the new version, only cells initialized as flammable are ever set to UNBURNT. Non-flammable cells are set to NON_FLAMMABLE and never change.

Therefore, the change is not in the ignite function itself but in how the grid is initialized.

Where is the change that prevents ignition of non-flammable cells?

Grid Initialization

grid = np.full((self.grid_size, self.grid_size), NON_FLAMMABLE, dtype=int)

grid[flammable] = UNBURNT

Only cells chosen as flammable (by the rho probability) are set to UNBURNT.

All others remain NON_FLAMMABLE.

Ignite Function

mask = self.grid == UNBURNT

…

ignition = (natural | human) & mask

self.grid[ignition] = BURNING

Only cells with

self.grid == UNBURNT(i.e., flammable) can ignite.

Non-flammable cells (NON_FLAMMABLE) can never be ignited, because they never satisfyself.grid == UNBURNT.In short:

The code change that prevents non-flammable cells from igniting is in the grid initialization, not the ignite function itself. The ignite function’s check (self.grid == UNBURNT) now only applies to the subset of cells that are flammable, because only those can ever be UNBURNT.

By the sound of it, the first explanation copilot gave wasn’t the best way to explain how the code had changed, maybe because I focused my prompt on the ignite function. So I challenged it, by prompting:

“”Therefore, the change is not in the ignite function itself but in how the grid is initialized.”. Okay, I agree. but then why did you change the ignite function?”

Copilot said:

Great catch! You are absolutely right—the core logic of the ignite function does not need to change if it was already using

self.grid == UNBURNTas a mask for ignitable cells. The original ignite function would already exclude non-flammable cells, provided the grid initialization ensures only flammable cells are ever set to UNBURNT.

So why did I present a different version?

That was an oversight in my explanation. The new and old versions are functionally equivalent as long as the mask is (

self.grid == UNBURNT). There is no need to change the ignite function if it already uses this mask, because:Non-flammable cells are assigned a different state (e.g.,

NON_FLAMMABLE = -1) and never set to UNBURNT.

The mask (self.grid == UNBURNT) will not select non-flammable cells, so they cannot be ignited.

Thanks for spotting this!

If your ignite function already usesself.grid == UNBURNT, it’s ready for the rho update, and only grid initialization (and possibly fire spread logic) need changing.

I should note here that I thought the code at this point was working as I wanted… although I later discovered it wasn’t. Given that the explanation wasn’t so convincing (and given that it is best practice), I asked co-pilot to write some unit tests:

“What unit tests should I run on the code in these files? please provide code for these tests”

Again, I had to push copilot to put these files in a more appropriate location (a src directory, for example) but, again, it wrote the code for the tests far faster than I ever would have been able.

After some other modifications (e.g. adding functionality from pylandstats to measure model output), I set to running the model for many different parameters with the aim of reproducing Figure 2 in Archibald et al. (2012)

I found a problem pretty quickly, that I asked co-pilot about:

“When p_spread = 1 and rho = 1 a single fire should burn the entire grid. But results are returning burned_fraction = 0.0005 Why is this?”

If

p_spread = 1andrho = 1, every cell is flammable and fire should spread to all adjacent unburnt cells with certainty. However, your results showburned_fraction = 0.0005, which is much less than expected.Possible reasons:

Ignition logic:

Yourignite()function only ignites one cell per fire event. If you run only one fire event per year, only one cell starts burning, and the spread happens only once before cells are updated to BURNT.

If you do not allow the fire to propagate for multiple steps, only a small number of cells will burn.How to fix:

Allow fire to propagate until no burning cells remain before igniting a new fire.

You can do this by loopingspread_fire()andupdate_burnt()until there are no burning cells left.Summary:

Your current code only allows fire to spread one step per fire event.

To burn the whole grid, let the fire propagate until no burning cells remain before starting a new fire.

Withp_spread=1andrho=1, this will result inburned_fractionclose to 1.

Copilot edited the code to match this proposed fix. It did not work. We tried a few other things and I suggested some additional unit tests to help me think through the problem.

For example, at one point I prompted:

“Thanks. After running the unit tests there are multiple failures. Something is not right in the code

- FAILED tests/test_fire_model.py::test_step_fire_full_burn – AssertionError: Not all cells burned when p_spread=1 and rho=1

- FAILED tests/test_fire_model.py::test_step_fire_partial_burn – AssertionError: Not all flammable cells burned

- FAILED tests/test_fire_model.py::test_burned_fraction_full_burn – AssertionError: Burned fraction not 1.0, got 0.05

- FAILED tests/test_fire_model.py::test_burned_fraction_partial_burn – AssertionError: Burned fraction not ~0.5, got 0.03773584905660377″

Copilot replied:

These failures indicate that fire is not propagating to all flammable cells as expected.

Withp_spread=1andrho=1, every cell should burn, but only a small fraction is burning.

Likely cause:

Yourignite()function ignites one cell, and thenstep_fire()lets the fire propagate.

However, the propagation logic inspread_fire()may be correct, but the initial grid may not be set to all UNBURNT cells, or the propagation loop is not working as intended.

Debug checklist

Grid initialization:

Make sure all flammable cells are set to UNBURNT at the start.Propagation loop:

Ensurestep_fire()keeps spreading fire until all reachable cells are burnt.Check for edge effects:

If the fire starts in a corner or edge, it should still reach all cells.

We went through this sort of thing several times. The suggestions co-pilot made were useful for me to check the code, but it clearly wasn’t working out the issue itself, and I was going to have to identify the problem. I narrowed the issue down to the propagation loop (as co-pilot suggested it might be), and spotted the issue:

“Is the problem that update_burnt incorrectly resets some newly burning cells to burnt so the fire then fails to spread properly?”

Copilot replied:

Yes, that is a likely cause of your problem.

Why?

Yourupdate_burntfunction:def update_burnt(self): self.grid[self.grid == BURNING] = BURNTThis sets all currently burning cells to burnt immediately after each spread step.

The issue:

In yourspread_firefunction, you create a mask new_burning for cells that should ignite in the next step.

You then set those cells to BURNING.

But in the next call toupdate_burnt, all cells that are BURNING (including those just ignited in this step) are set to BURNT immediately.

This means newly ignited cells do not get a chance to spread fire in the next step—they are burnt before they can propagate.

Correct approach:

You need to distinguish between cells that were burning at the start of the step (and should be set to burnt), and cells that have just become burning (and should remain burning for the next spread).

How to fix:

Refactor your fire update logic so that:Only cells that were burning at the start of the step are set to burnt.

Newly ignited cells remain burning for the next spread.

One way to do this is to:Track burning cells before the spread.

After spreading, set only those to burnt.

Example fix:

def step_fire(self): if not np.any(self.grid == BURNING): self.ignite() while np.any(self.grid == BURNING): burning_indices = np.argwhere(self.grid == BURNING) self.spread_fire() # Only set cells that were burning before the spread to BURNT for x, y in burning_indices: self.grid[x, y] = BURNTSummary:

The bug is that

update_burntburns new cells too early.

Fix by only burning cells that were burning at the start of the step.

This will allow fire to propagate correctly through the grid.

Let me know if you want the full refactored code!

Note, copilot phrases it as ‘my’ (James’) problem in ‘my’ (James’) update_burnt function code… that copilot itself wrote!

That feels frustrating, but gets to the crux of the point. As a human it seems intuitive that copilot should understand the code, given that it produced it, but really it doesn’t.

It might feel frustrating that previous code produced by copilot is seen as ‘mine’, but maybe that’s actually a useful way to think about it. Even though I didn’t write it myself, the code is mine in the sense that it is doing (or trying to do) what I want it to do. Copilot doesn’t care about the intention of the code, it is producing the code because I asked it to.

So really, yes, it was my problem in my code! And while copilot made some useful suggestions, it was I (James) that had to work out (reason about) how to fix it myself.

[Yes, I need to work out how to better export chats from copilot to blog!]